Gustav III and the Museum of Antiquities

King Gustav III's collection of ancient sculptures has an eventful history, including a volcanic eruption, degenerating excavations, incognito royal travel, a meeting with the Pope and the opening of Europe's first art museum.

When Vesuvius erupted in 79 AD, several towns and villages at the foot of the volcano were buried in lava and ash. The largest of the towns was Pompeii, which was "rediscovered" in the 1740s.

When the excavation of Pompeii started in 1748, a number of key discoveries were made that increased knowledge about antiquities.

Growing interest in the ancient world

From this point in time a reaction grew against the dominating style of the era – rococo. This was not only due to the excess of rococo, inspired by shells and scroll-like forms, but also because of its shallowness and affectation.

Rococo gave way to Neoclassicism, described as being of high moral stature, noble austerity and harmonic beauty. The classical art of construction once again became a role model and this neoclassicism kept close to the role models of renaissance and baroque architecture.

Greek art and architecture served as guidance. And most admired and imitated of all was the Doric style, calm and restful in its steadfastness. The rising interest in the ancient world also lead to excavations in and around Rome, which at times degenerated into a pure treasure hunt.

Gustav III's "Le grand tour"

Sculptures and fragments of architecture were highly sought after in the world of art dealers. The market was dominated by the Holy See and well-to-do customers outside Italy, primarily royal houses and nobility.

Purchases were made in conjunction with the almost obligatory educational journeys that were made, "le grand tour".

The Swedish King Gustav III also made such a journey southbound, heading for Italy and Rome. The trip took place quite late in his life and lasted from September 1783 to August 1784, approximately half of which time was spent in Italy.

Even though he travelled incognito as the Count of Haga, it was already known that the Swedish King was a prospective buyer of marble sculptures and art objects.

On New Year's Day in 1784, Gustav III and his entourage were shown the collection of ancient sculptures in the Vatican, Museo Pio Clementino. Their guide was no less than Pope Pius VI himself.

The Pope and the Gallery of Muses

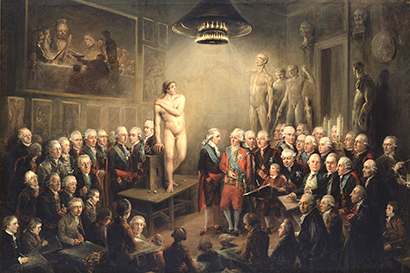

The visit to the papal Gallery of Muses served as guidance for Gustav III's acquisitions of ancient statues and their later exhibition after his death in 1792. Gustav commissioned artist Bénigne Gagneraux to depict the meeting with the Pope.

As those who were carrying out the excavation and restoration of the antiquities knew that Gustav III wished to acquire an Apollo statue and nine female statues, they made sure to provide him with what he wanted!

Not all the muses were originally created as muses, but were complemented and provided with the suitable attributes by art dealers and those carrying out the restoration. They were also skilful at concealing fractures and joints from added sections.

When visiting Gustav III's Museum of Antiquities as an authentic museum from the 1790s, it is important to know that additions made in the 1700s have not been removed, a practice that has been carried out with similar sculpture collections in other museums.

It is also important to remember that all objects, with the exception of their additions, are of classical origin and that most of the larger statues are more or less free Roman interpretations of Greek motif.

The collections are opened to the public

The collection was intended for Gustav III's planned palace in Haga. However, when the collection of a few hundred objects – not only sculptures but also vases – was shipped to Stockholm, it was first installed in the state rooms at the Royal Palace of Stockholm.

Sweden, having previously been devoid of classical sculptures, had now suddenly been enriched. In order for the collection to be useful from an educational perspective, it was also made available to a certain extent to artists and interested amateurs from the upper classes.

When Gustav III died on March 29 1792 following an assassination attempt two weeks earlier at a masquerade ball, it took just three months for the government to decide to establish a museum dedicated to antiquities.

According to the charter of the foundation that established the museum, it was founded as a tribute to the dead king "for his efforts as a protector of art in his lifetime".

The museum's first curator was Carl Fredrik Fredenheim, who at that time was the most qualified person in the country for the position. He had already assisted Gustav III in the acquisition of the collection and was one of the first to carry out systematic excavations at the Forum Romanum in Rome.

The opening of the Royal Museum

The northeast palace wing was designated as the location for the new museum – exactly the same spot where the collection is displayed today.

Nicodemus Tessin the Younger would most likely have preferred the Orangery at Ulriksdal instead. However, the location at the Royal Palace of Stockholm meant that the architect Carl Fredrik Sundvall did not need to make any extensive changes to adapt the rooms to the requirements of a museum.

In 1794 the museum was ready to open to the public. It was one of northern Europe's first art museums, and named "the Royal Museum" even though it was public property belonging to the Swedish State.

The museum changed character in the 1800s in that space was made for modern sculptures of the period. Artists such as Johan Tobias Serge, Niclas Byström and Erland Fogelberg exhibited their work in the museum.

The collection grows

However, a more significant change took place around 1840 when the smaller inner gallery was used for exhibiting oil paintings. In conjunction with this the interiors were revamped. Cupboards and shelves disappeared and the room was given a new colour replacing that from the 1700s.

Later, as the collection of art grew, it became clear that the museum space at the palace was not large enough. After long and drawn out debates the government finally resolved to finance a new museum building, which was inaugurated in 1866.

The new museum, to which the Royal Museum's collection was transferred, was given the name National Museum (National Gallery). It was a suitable name as the museum, in addition to housing art collections, also was intended to house the state's Historical Museum, the Coin Cabinet and the Royal Armoury.

The former rooms of the Royal Museum were taken over by the Royal Library, which already used the rooms above the museum. When the library was given its own building in Humlegården in 1877, the museum was rebuilt to house the Royal Armoury collections, which were exhibited here between 1884 and 1906.

Re-establishment and reopening

After 1906, the museum was used for various purposes. In the 1950s, however, it was realised that responsibility must be taken for the former Royal Museum and that it was indefensible to allow these architecturally classical rooms to remain closed to the public.

The initiative to return Gustav III's collection of antiquities to their original home was partly taken by the National Museum and by the Office of the Governor of the Royal Palaces.

The king at that time, Gustaf VI Adolf, was enthusiastic about the idea and palace architect Ivar Tengbom was responsible for the renovation.

In 1958 the museum opened its doors once again to the public, now under the name Gustav III's Museum of Antiquities.

The renovation carried out in the 1950s mainly encompassed the large gallery and the gallery of the muses – not the entire museum. Therefore, in 1992, in conjunction with the celebration of 200 years since the inauguration of the museum, it was only natural that a full restoration of the original Royal Museum should be carried out.

This was made possible thanks to well preserved pictures, drawings and other archive material that guaranteed the original positioning of objects, architecture, colours and other decorative details.

Photo, top image: Oil painting by Pehr Hilleström in 1796, the National Museum's collection.

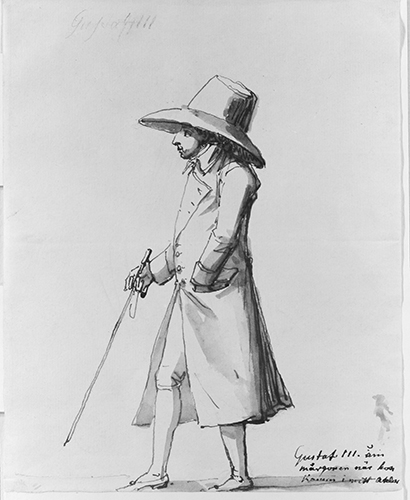

"Gustaf III in the morning when he comes to my studio." Drawing by sculptor and painter Johan Tobias Sergel, circa 1779. King Gustav III played a significant role in the promotion of art and culture. Photo: The National Museum

The contemporary admiration for classical art aroused the interest of the king, taking him on a journey that lasted almost a year. Photo: Lisa Raihle Rehbäck

The Vatican's collection of sculptures inspired King Gustav III, and was shown to the king by the Pope himself. The meeting with the Pope in the Gallery of Muses, as depicted by the French artist Bénigne Gagneraux. Photo: Erik Cornelius, the National Museum

King Gustav III's most expensive acquisition for the collection: Endymion, who sleeps eternally. Photo: Lisa Raihle Rehbäck

An example from the collection of the additions made in the 18th century. Here, the head of the Prince of Troy has been attached to the body of the goddess Isis and transformed with added attributes into Calliope, the muse of epic poetry. You can read more about the muses in our Archive (double click on the image).

King Gustav III made his collection available for the purposes of study. Artists and interested amateurs from the higher levels of society were invited to study the sculptures at the palace. The image shows King Gustav III's visit to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, as depicted by Elias Martin in 1782. Photo: The Royal Academy of Fine Arts

In 1794, two years after the death of King Gustav III, the art museum was ready to be opened. This makes it one of the oldest museums in Europe. Detail from Pehr Hilleström's oil painting "Museum at the Royal Palace", the inner gallery, 1796. Photo: The National Museum

In 1866, the collection was moved to the newly built National Museum. The stone galleries at the palace become home to the Royal Library instead, and subsequently to the Royal Armoury's collection. 1904 photo of the large gallery, from the archive of the Bernadotte Library.

The Museum of Antiquities was re-opened in its original location at the Royal Palace of Stockholm in 1958. The photo shows the celebration of the museum's 200th anniversary and restoration on 28 June 1992, with King Carl XVI Gustaf, Queen Silvia and Director of the National Museum Olle Granath.

Today, the sculptures are positioned where they were originally displayed. Photo: Alexis Daflos

The museum consists of the larger and smaller stone galleries in the northeast wing of the palace. Photo: Alexis Daflos

The Museum of Antiquities is open during the summer, and is included in the palace ticket. Visitors can buy a guide, and audio guides in Swedish and English can be borrowed free of charge. You can also take a 360° virtual tour of the larger gallery here on the website – see the link in the info box. Photo: Lisa Raihle Rehbäck